“Don’t be so sure I’m as crooked as I’m supposed to be.”

- Spade to Brigid O’Shaughnessy, during their final discussion in The Maltese Falcon.

S Spade made its debut over CBS in August of 1946, personable

Spade made its debut over CBS in August of 1946, personable

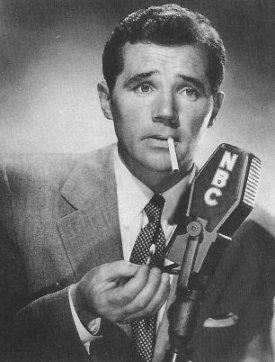

Howard Duff, a comparative unknown in Hollywood circles, was assigned the title role. The selection of young Duff for the hard-hitting detective was perfect casting, his success

was immediate, and Hollywood began predicting important things to come for this new personality.

Just one year after his “Sam Spade” debut, Howard Duff found himself under personal contract to Mark Hellinger, movie producer. His first screen role as “Soldier” in material from critics throughout the country. Duff received on-screen credit as “radio’s Sam Spade.” Even when Duff

was given offers for movie roles, he never gave up the radio juggle both acting mediums.

The enormous success of the Sam Spade radio program, spawned a series of comic strips, magazine articles and radio cross-overs, and Universal Studios even considered the possibility of making a Sam Spade movie with Duff in the lead.

All this and much more because of a single radio program, based on a fictional detective glamorized in one novel, three short stories, and the 1941 motion-picture, The Maltese Falcon. Dashiell Hammett, the creator of fictional private eye, received royalty checks for the use of his character of Sam Spade, but had no direct involvement with the series except the lending of his name in the opening and closing credits.

Howard Duff’s big break came in the spring of 1946. William Spier, producer/director of the CBS radio program, Suspense, was involved in bringing Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade character to the airwaves. Spier was looking for that perfect voice - the persona who could best represent the character he had in mind.

“The most memorable moment of my life came when I was at my lowest spirit,” Duff recalled in a column for the National Enquirer in 1957. “It was right after World War II, and, like a million other guys, I was back home with an honorable discharge and no job. I wanted to be an actor. Day after day, I made the rounds of radio studios and always received the standard brushoff. Eating regularly became a problem for me.”

“Then one day, when I was discouraged, disgusted and hungry, I dropped into a producer’s office to try out for a role on a forth-coming radio program about the adventures of a tough private detective,” Duff continued. “There must have been at least 100 other guys jammed in that office waiting to read for the Sam Spade role. I even recognized a few famous faces in the crowd, and it threw me into even a greater melancholy. By the time my turn came I was feeling real mean, and about as low as a patrolman’s instep. When they handed me the script and told me to go ahead, I delivered the lines in a half-snarling, half-bored manner like a guy reading a grocery list. I put no punch into my delivery because I just didn’t care any more about getting a job as an actor.”

Spier was not initially impressed with Duff’s performance, but his wife, Kay Thompson, became so enthralled with Duff’s interpretation of the Sam Spade character that she continued to lobby on her husband, until he relented. “Two days later, the producer of the Sam Spade show phoned me,” Duff recalled. “‘You’ve got the job,’ he told me, ‘You sound just the way we want Sam Spade to sound. You’re a natural for him.’ Becoming Sam Spade, private eye, for radio fame, was the greatest moment in my life. It just goes to prove what luck can happen to a guy when he least expects it.”

An audition record was made, dated May 1, 1946, and Howard Duff played the title role. The script was entitled “Sam Spade and the Walls of Jericho,” and scripted by Bob Tallman and Jo Eisinger.

The audition cinched a sponsor, Wildroot Hair Tonic, and a network, the American Broadcasting Company. The recording was never broadcast on the air, leaving the radio audience (and fans) to this day wondering just what the plot was, and the opportunity to hear Howard Duff make his dramatic appearance as Sam Spade. Both the audition record and the first few broadcasts of the series gave no air credit for the writers. Spier intended to convince the network, ABC, that Dashiell Hammett was personally involved with the episodes, since the contract between Spier and Hammett stated the author’s name would be employed in the epigraphs each week.

Of the 13 episodes broadcast on ABC, seven were Bob Tallman - Jo Eisinger originals; the remaining six were adaptations of Hammett’s short stories. Tallman and Eisinger never received writing credit for any of the ABC broadcasts.

The 13 episodes broadcast over the ABC network were perhaps some of the best of the series. The plots were clever and intricate. Spade’s clients had little ethics and when the situation called for desperate means, Spade threw his good intentions out the window.

The premiere broadcast, “Sam and the Guiana Sovereign,” was an original script by Tallman and Eisinger, and played much like The Maltese Falcon with a cast of shady characters, stooping to betrayal and murder to gain possession of a valuable artifact. Shortly after newspapers report the murder and robbery of Bernard F. Gilmore, Sam finds himself hired by Gilmore’s business partner, Emil Tonescu, to find the Guiana Sovereign that was stolen from the dead man. The Sovereign has sentimental value, according to Tonescu, who wishes to have it returned. Naturally, Sam meets enough suspects to fill a tabloid, only to discover that Gilmore is alive and well, in hiding. He survived the murder attempt, wounded from a gun shot, and prefer to remain in hiding when he learns that his assailant was Cara Kenbrook, a former business partner in Trinidad. Before Sam learns of Cara Kenbrook’s involvement, Tonescu is murdered by Gilmore, and Sam uncovers all the motives - including blackmail.

Sam’s methods are unorthodox, as revealed when he pushes the corpse of Tonescu into a closet, cleaning the scene of the crime to baffle the police, and drinking rum and coke and a shot while on duty.

There were a few lines scratched out of the script, that never got aired, including one where Sam takes Lina’s money to exchange for helping return the coin to her, even though he was hired by Tonescu to do the same. (A similar scene in which Sam took Brigid O’Shaughnessy’s money in The Maltese Falcon.) Another deleted scene was when Effie asks about the thousand dollars he earned on the case, and Sam explains that he lost it all on a horse race.

The second broadcast of the series, “Sam and the Farewell Murders,” broadcast July 19, 1946, was the first of many episodes adapted from a Dashiell Hammett story. Though Hammett had no participation in the radio productions, many of his short stories were adapted (or in some cases the plots were lifted) from short stories already published in magazines and periodicals.

This episode, adapted from “The Farewell Murder” (originally published in the February 1930 issue of Black Mask), concerns Miriam Farewell, who hires Sam to visit her father-in-law, the great, wealthy Carter P. Farewell, whose life has been threatened by a poison pen letter. After one failed murder attempt, she fears the culprit will try again. The lead suspect is Farewell’s neighbor, Captain Sherry, an Englishman, who was drummed out of the Army years ago because of Mr. Farewell’s former shady business ventures. When the old man is found murdered, the police are unable to pin the crime on Captain Sherry.

Spade and Miriam visit the hotel where Sherry is staying, only to find him dead from a bullet to the head, and Dolph, Miriam’s husband, with a gun in his hand. While Spade phones Lt. Dundy, Dolph jumps out the window, taking his own life. Dundy arrives at the scene and Spade explains how Dolph didn’t jump out the window - he was pushed by Miriam when Spade was on the phone in the other room. She planned the death of her father-in-law so she could collect her inheritance, and attempted to cover her tracks with a second murder. In this broadcast, Spade romantically kisses Miriam, a married woman. (Miriam was still married to Dolph at the time.)

Throughout the broadcasts, actor Howard Duff fit the description of Sam Spade to a tee. The radio audience apparently liked his character, as did the trade papers that began publishing photos of the actor in costume, including the hat. Duff didn’t just sound like Spade - he looked like the private detective. The actor stood six feet and a half inch tall, weighed 183 pounds, brown hair and blue eyes. A conservative dresser, quiet in speech and manner, Duff took his away-from-work relaxation in the company of old friends. He was lazy and he admitted it to his friends, even dating women and trying to dodge the photographers . . . the way Spade led much of his life.

The third broadcast of the series, “Sam and the Unhappy Poet,” offered a brief glimpse of Spade’s one-liners that would become the jovial trademark of the series. Spade receives a visit from Eli Haven, a dramatic poet, who feels the shadow of death tailing his every move. Asking for Spade to hold an envelope for him, and open it only when the papers report his death, Sam cannot figure out the paying client’s motives - at first.

HAVEN: There is one thing you can do for me, Mr. Spade. Take this envelope. Hold it for me.

SPADE: Sure.

HAVEN: Thank you, sir. Life is but a ferris wheel.

SPADE: Feels like there’s nothing in it.

HAVEN: It contains nothing but a whisper, so long as it remains unsealed.

SPADE: And if it doesn’t remain sealed?

HAVEN: Like an evil Genii, it will escape and grow, first into a shout, then into many shouts,

and then into a mighty roar.

SPADE: When will you be back for it?

HAVEN: It wants a quarter to twelve. And tomorrow’s doomsday.

SOUND: CHAIR PUSHED BACK

HAVEN: Thank you, Mr. Spade. Miss Perrine – it’s no longer dark. When I walk out this door, I

shall be walking into the sun. Goodbye. Goodbye.

SOUND: QUICK STEPS OUT OF ROOM. DOOR OPENS AND CLOSE

SPADE: That’s what comes of not learning a trade.

In “Sam and the Psyche,” the fourth episode broadcast, Dr. Gregory Denolph hires Sam to help retrieve some letters that might incriminate one of his patients, Constance Brent, the famous actress. Sam agrees to work for the doctor, but when he visit’s the doctor’s office, he learns that homicide is labeling Dr. Denolph’s death a suicide. Denolph’s widow insists it was murder, and suspects Constance was guilty of the crime. Sam questions all of the suspects, including Jonathan Walters, a rival psychiatrist.

WALTERS: Now what do you want with my wife?

SPADE: I’ve come to tell her that Dr. Denolph is dead.

WALTERS: Are you sure?

SPADE: You try falling from a 12-floor window sometime.

NOW LET’S SKIP TO “THE SAM SPADE CAPER”

By 1949, Wildroot still sponsored the program, satisfied with the results they were paying for, and CBS had another radio program in their prime-time lineup to be proud of. But like many successful radio programs, the network was not without complications.

In 1930, Judge Learned Hand suggested in a court ruling that fictional characters, as well as the plot to a literary property, could be copyrighted. Warner Bros. Studio, having filmed three previous versions of The Maltese Falcon, used Hand’s ruling as the backbone for laying claim to the ownership of the novel, believing it owned all the rights to the story and the characters contained within. Dashiell Hammett and Alfred A. Knopf, the publisher of The Maltese Falcon, sold the movie studio the exclusive rights to the story in movies, radio, and television. Naturally, the studio assumed they owned the entire property.

Years later, in 1946, both Hammett and Knopf sold the exclusive right to produce a radio version of the Sam Spade character, to the American Broadcasting Company (transferred to the Columbia Broadcasting System shortly after). After hearing the broadcasts over CBS, Warner Brothers then sued Hammett, Knopf, and the radio network, claiming that they owned the exclusive rights to the Sam Spade character under their prior contract with Hammett.

The studio contended that the radio show was an unauthorized use of the character, and sued the studio under the grounds of copyright infringement. Hammett argued that Warner Bros. had purchased only the motion-picture rights. Since the movie studio would not back down, the case was dragged to court while the radio program continued its weekly course.

Known as “The Sam Spade Case,” the studios, Warner Bros. Pictures Inc. and the Columbia Broadcasting System, battled over the ownership to the Sam Spade character for years. The legal heads of CBS were used to handling infringement suits from outside parties, so Warner Bros. Pictures v. Columbia Broadcasting System (9th Cir. 1954) 216 F.2d 945, 951 was nothing new to the network.

In 1949, a New York court decided in favor of Warner Bros. Legal council for CBS continued to fight the ruling. In 1954, three years after the radio program ceased broadcast, the Ninth Circuit Court held that Hammett had not in fact granted Warner Bros. the exclusive right to the character of Sam Spade. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals covered a substantial part of the movie and broadcasting industry. “The characters were vehicles for the story told,” it said, “and the vehicles did not go with the sale of the story.”

SAM SPADE SALUTES

While CBS was fighting Warner Bros. over the ownership to the character of Sam Spade, radio programs continued to feature spoofs of both the movie and the radio series, with Howard Duff occasionally appearing in character. On the evening of December 5, 1946, William Spier marked a highlight on his Suspense program when he offered a spooky drama entitled “The House in Cypress Canyon.” The tale concerned a real estate agent who invites a friend of his, a detective named “Sam,” to listen to a transcription made by a young couple who just purchased their new home. The tale involved a werewolf that howls at night. While the last name of the detective is not given, the actor playing the role is Howard Duff. This was one of William Spier’s in-jokes.

Though subject of debate on the world wide web (the internet), whether or not it was Sam Spade on that particular Suspense episode, the fact remains that Spier arranged for Duff to play the role of a detective named Sam and most likely, to avoid paying royalties for an additional Sam Spade broadcast, avoided using the “Spade” name during the broadcast. “The House in Cypress Canyon” is now considered by old-time radio fans as one of the 10 best episodes of the Suspense program, and one of the 10 most frightening horror radio broadcasts of all time.

Howard Duff did assist other radio programs spoof the Sam Spade character on variety/comedies. On the October 22, 1947 broadcast of Philco Radio Time, starring Bing Crosby, guest Clifton Webb starred as “Clifton Web: Private Face, Eyes, Ears, Nose and Throat of Crime.” Howard Duff appeared in the middle of the skit as Sam Spade. On the January 24, 1948 broadcast of Joan Davis Time, Joan falls asleep, and dreams she is involved with a caper with private detective Sam Spade, also played by Howard Duff. On the February 10, 1949 broadcast of Maxwell House Coffee Time, George Burns and Gracie help Sam Spade, played by Howard Duff, solve the murder of a shady character named Mr. Benson.

THE YOURS TRULY, JOHNNY DOLLAR CONNECTION

In early 1949, Gil Doud began scripting for the radio program, Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar. Borrowing a few of the plot lines and motives from episodes of Sam Spade, Doud rewrote the stories to fit the Johnny Dollar mold. Two episodes from the program‘s first season on the network, however, scripted by Gil Doud, spoofed the Maltese Falcon caper to a tee.

“The Case of the Slow Boat From China,” broadcast February 25, 1949, Johnny Dollar, an insurance investigator, visit’s the country of Singapore to help expedite a shipment of tin, only to meet up with suspicious and shady characters all searching for the mysterious “it.” One of the shady individuals sounds like Casper Gutman, and in one scene, Johnny comments that “Your mother must have been frightened by Sydney Greenstreet.”

“The Disappearance of Twelve Apex Cabs,” broadcast July 24, 1949, definitely contains shades of The Maltese Falcon, and the Sam Spade radio program. The episode was subtitled, “Who Took the Taxis for a Ride?” Many of the Sam Spade radio broadcasts feature a humorous subtitle, courtesy of the script writers. Numerous shady characters are once again in search of a valuable artifact, this time referred to as “The Scarlet Madonna.” One of the individuals searching for the artifact, bears resemblance to Sydney Greenstreet’s character, and is named “Fat Stuff.”

AND NOW A SAMPLE FROM THE EPISODE GUIDE . . .

Episode #5 “DEATH AND COMPANY” Broadcast August 9, 1946

Plot: Martin Chappel turns to Sam and the police for help. His wife has been kidnapped and a ransom demand has been made by an organization that refers to themselves as “Death and Company.” When the ransom payoff fails, Sam blames the police for their bungling. When Mona Malloy hires Sam to find her husband, wanted on six counts, so she can divorce him, Sam finds Eddie Malloy’s empty apartment - including the body of Chappel’s dead wife. Sam suspects both cases are connected and sets about finding Eddie Malloy, who saves his life after Sam proves that Mona was having a fling with Martin Chappel, and intended to murder Chappel’s wife figuring the police would add the murder to Eddie Malloy’s list of crimes.

Trivia, etc. Mona was a receptionist at the Blue Bottle Bar and Grill in this episode, which plays an important part in the mystery. Sam describes the place as “one of those dark joints with a lot of neon behind the bar, a dance floor in the separate back room with booths around it, and a juke box big enough for a family of midgets to keep house in.” This marks the first time the Blue Bottle Bar and Grill is featured on the series. It would be mentioned in numerous episodes.

Towards the end of the drama, when Sam calls Mona to play a record, she is unable to play the transcription and comments: “Here is a new number that has just come in. Lud Gluskin and his Versatile Juniors . . . Would you like that, sir?” Lud Gluskin was the musical director for the Sam Spade series, and his name would occasionally come up in the scripts as inside-jokes. This was the first of many.

This episode was adapted from the non-Sam Spade short story, “Death and Company,” written by Dashiell Hammett, originally published in the November 1930 issue of Black Mask.

Episode #6 “TWO SHARP KNIVES” Broadcast August 16, 1946

Plot: When an old friend dies in Sam’s office, Sam recounts to Effie his past as a lieutenant detective in a mid-west state, where his old friend, Wally, was the mastermind behind a murder and a large payoff. It seems Lester Furman arrived in town, and Sam and Wally picked him up, having seen a circular claiming Furman was wanted in Philadelphia for an unanswered murder charge. When Furman was found the next morning in his cell, hung to death, Sam learns from the coroner that the suicide was really murder. After questioning Furman’s wife, Sam discovers that his partner, Wally (alias Harry West), was Mrs. Furman’s lover. Wally faked the circular, arranged for Sam and he to pick up Furman at the train station, and the murder, so he and Furman’s wife could inherit a small fortune.

Trivia, etc. Dashiell Hammett wrote a short story entitled “Two Sharp Knives,” originally published in the January 13, 1934 issue of Collier’s. For this episode of The Adventures of Sam Spade, the authors, Tallman and James, adapted the short story into a flashback sequence, incorporating Sam’s character into the plot, and told through the use of a flashback dating before Sam became a San Francisco private detective. Only one other episode featured a story taking place before Sam went into private practice, “Inside Story of Kid Spade,” broadcast a few months after this episode.

The same short story, “Two Sharp Knives,” was adapted for radio’s Suspense, also under the direction of William Spier, and broadcast twice before this broadcast, on December 22, 1942 and June 7, 1945. The Suspense adaptation was scripted by John Dickson Carr. This is also one of the few episodes of the Sam Spade series to feature Effie taking a drink of alcohol. Effie's character was capable of drinking and smoking, as evident in The Maltese Falcon (1929), however this depiction changed after the earliest episode of the radio program, making Effie more innocent through the rest of the series.

Episode #7 “ZIG ZAGS OF TREACHERY” Broadcast August 23, 1946

Plot: Shortly after Dr. Herbert Estep hands Sam an envelope and asks him to deliver it to the district attorney, Sam is knocked unconscious from behind and the envelope is stolen. When the doctor is found dead, Sam begins questioning the usual suspects: Vance Richmond, the doctor’s attorney; Edna Estep, the doctor’s first wife; Mr. Estep, his recent wife who was accused of the murder; and Jonathan Boyd, a drunk who thinks he is a doctor. After Boyd is found dead from a hit-and-run, Sam pieces the clues together to form the solution to the crime. Dr. Estep sold his license to practice to a drunk, who moved about from town to town one step ahead of the law, setting up a practice. The attorney was blackmailing his client for silence, and after fifteen years of scamming, when the secret was going to go public, murder was done to cover the evidence.

Trivia, etc. This episode was based on the short story of the same name by Dashiell Hammett, originally published in the March 1, 1924 issue of Black Mask. The title partly from narration given by Spade: “His trail across town was like a tanker on a zig-zag course, two jumps ahead of a U-boat.”

Sam does not refer to this case as the “Zig Zags of Treachery.” Instead, he refers to it as “The Murder of Dr. Estep” and after the middle commercial, the announcer refers to the drama as “Zig Zags of Treachery” but the title was scratched out on the script and “The Murder of Dr. Estep” was penciled in. Unsure of which title this episode goes under, I am going by the title on the cover of the script but leaving a notation that it is possible that this episode might go under the other title.

To order a copy of this book, simply mail a check or money order payable to:

Sam Spade Book

Po Box 189

Delta, PA 17314

Cost of the book is $24.95 plus $4.80 postage.

Paypal is accepted.